-40%

RARE Manuscript Letters 1859 Oneida Community NY Bottles Lancaster Glass Works

$ 525.36

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

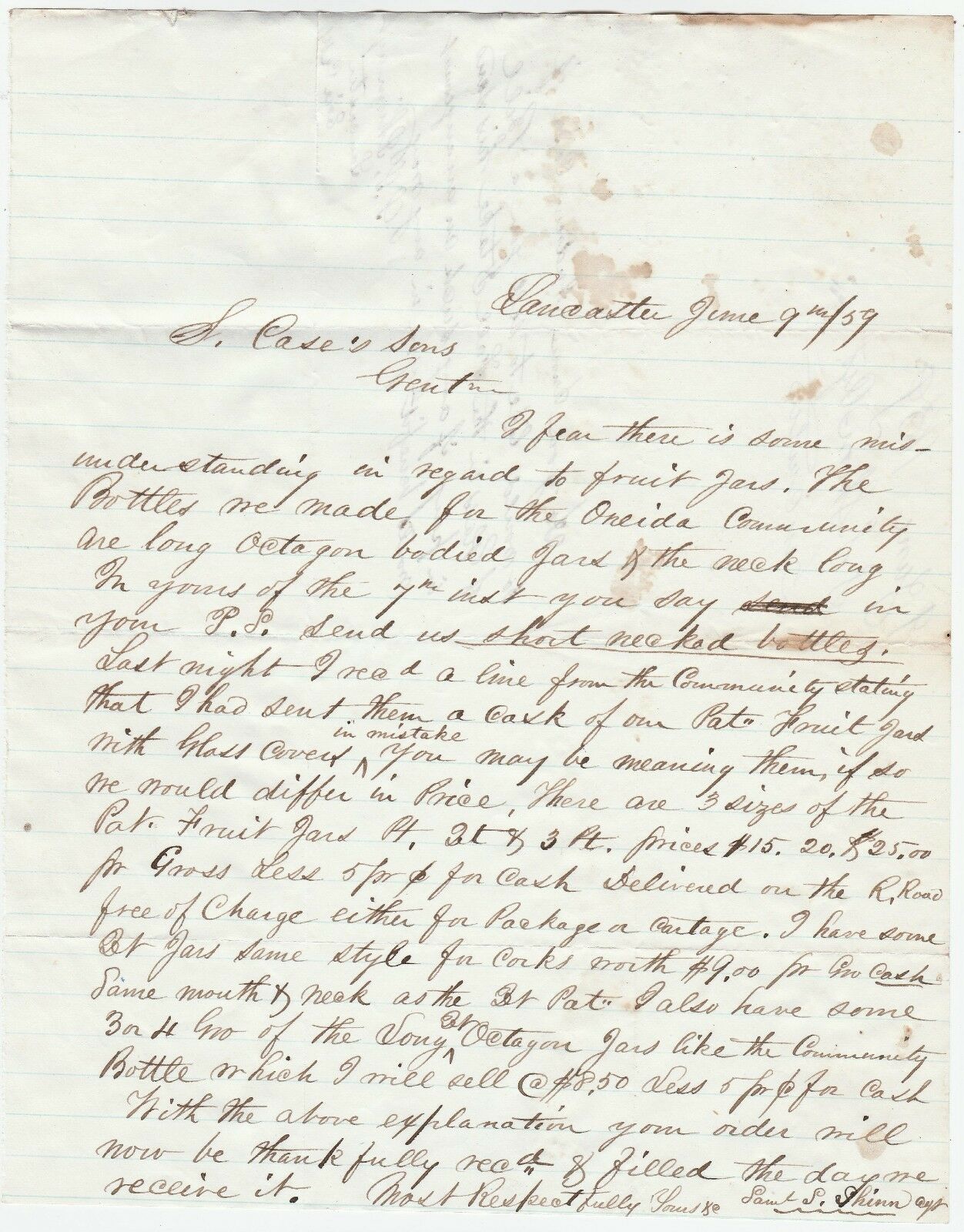

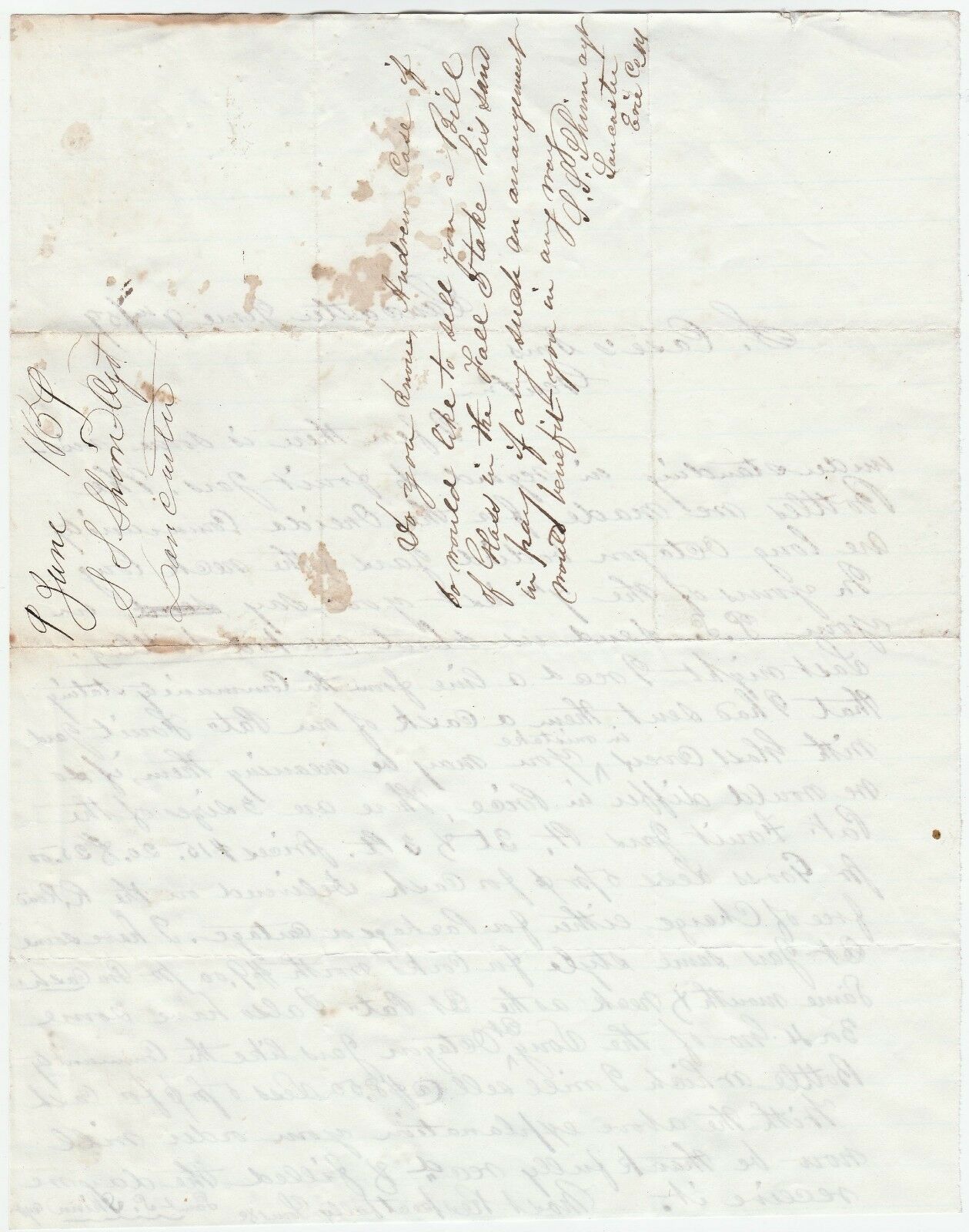

RARE Autograph Letter LOTTwo Letters

Regarding Bottles Made for the Oneida Community (

Oneida, NY)

by Lancaster Glass Works

Lancaster, New York

1859

For offer, an original old manuscript letter lot. Fresh from an estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now.

Vintage, Old, antique, Original -

NOT

a Reproduction - Guaranteed !!

These letters were unearthed from a collection of letters found in a local estate, all folded up for many years. Originally from the Case business, in Vernon, NY (Salmon Case, and later S. Case's Sons). Two autograph letters, signed. Written by Samuel S. Shinn, representing the Lancaster Glass Works (which would burn down this same year), and bottles made for the Oneida Community (see below for more on this interesting religious sect that later formed as the company that would make silver and other items). The bottles are quite rare, and are marked with an OC. The octagon fruit jars mentioned in this letter were probably used by the Oneida Community to sell fruit juice. The important content of these letters adds interesting historical details that were previously unknown. ALS.

In good to very good condition. Fold marks (NOTE - these will be sent folded up, as found, to save on shipping), small rip at top of one letter. Please see photos for details.

If you collect Americana history, American 19th century Civil War era

, MS document related, etc., this is one you will not see again. A nice piece for your paper / ephemera collection. Perhaps some genealogy research information as well.

Combine shipping on multiple bid wins!

1547

The Oneida Community was a perfectionist religious communal society founded by John Humphrey Noyes in 1848 in Oneida, New York. The community believed that Jesus had already returned in AD 70, making it possible for them to bring about Jesus's millennial kingdom themselves, and be free of sin and perfect in this world, not just in Heaven (a belief called perfectionism). The Oneida Community practiced communalism (in the sense of communal property and possessions), complex marriage, male sexual continence, and mutual criticism. There were smaller Noyesian communities in Wallingford, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersey; Putney and Cambridge, Vermont.[1] The community's original 87 members grew to 172 by February 1850, 208 by 1852, and 306 by 1878. The branches were closed in 1854 except for the Wallingford branch, which operated until devastated by a tornado in 1878. The Oneida Community dissolved in 1881, and eventually became the giant silverware company Oneida Limited.[2]

Community structure

Even though the community only reached a maximum population of about 300, it had a complex bureaucracy of 27 standing committees and 48 administrative sections.[3]

The manufacturing of silverware, the sole remaining industry, began in 1877, relatively late in the life of the community, and still exists.[2] Secondary industries included the manufacture of leather travel bags, the weaving of palm frond hats, the construction of rustic garden furniture, game traps, and tourism.

All community members were expected to work, each according to his or her abilities. Women tended to do many of the domestic duties.[4] Although more skilled jobs tended to remain with an individual member (the financial manager, for example, held his post throughout the life of the community), community members rotated through the more unskilled jobs, working in the house, the fields, or the various industries. As Oneida thrived, it began to hire outsiders to work in these positions as well. They were a major employer in the area, with approximately 200 employees by 1870.

Complex marriage

The Oneida community believed strongly in a system of free love (a term Noyes is credited with coining) known as complex marriage,[5] where any member was free to have sex with any other who consented.[6] Possessiveness and exclusive relationships were frowned upon.[7] Unlike 20th-century social movements such as the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s, the Oneidans did not seek consequence-free sex for pleasure, but believed that, because the natural outcome of intercourse was pregnancy, raising children should be a communal responsibility. Women over the age of 40 were to act as sexual "mentors" to adolescent boys, as these relationships had minimal chance of conceiving. Furthermore, these women became religious role models for the young men. Likewise, older men often introduced young women to sex. Noyes often used his own judgment in determining the partnerships that would form, and would often encourage relationships between the non-devout and the devout in the community, in the hopes that the attitudes and behaviors of the devout would influence the non-devout.[8]

In 1993, the archives of the community were made available to scholars for the first time. Contained within the archives was the journal of Tirzah Miller,[9] Noyes' niece, who wrote extensively about her romantic and sexual relations with other members of Oneida.[1]

Mutual criticism

Every member of the community was subject to criticism by committee or the community as a whole, during a general meeting.[10] The goal was to eliminate undesirable character traits.[11] Various contemporary sources contend that Noyes himself was the subject of criticism, although less often and of probably less severe criticism than the rest of the community. Charles Nordhoff said he had witnessed the criticism of a member he referred to as "Charles", writing the following account of the incident:

Charles sat speechless, looking before him; but as the accusations multiplied, his face grew paler, and drops of perspiration began to stand on his forehead. The remarks I have reported took up about half an hour; and now, each one in the circle having spoken, Mr. Noyes summed up. He said that Charles had some serious faults; that he had watched him with some care; and that he thought the young man was earnestly trying to cure himself. He spoke in general praise of his ability, his good character, and of certain temptations he had resisted in the course of his life. He thought he saw signs that Charles was making a real and earnest attempt to conquer his faults; and as one evidence of this, he remarked that Charles had lately come to him to consult him upon a difficult case in which he had had a severe struggle, but had in the end succeeded in doing right. "In the course of what we call stirpiculture", said Noyes, "Charles, as you know, is in the situation of one who is by and by to become a father. Under these circumstances, he has fallen under the too common temptation of selfish love, and a desire to wait upon and cultivate an exclusive intimacy with the woman who was to bear a child through him. This is an insidious temptation, very apt to attack people under such circumstances; but it must nevertheless be struggled against." Charles, he went on to say, had come to him for advice in this case, and he (Noyes) had at first refused to tell him any thing, but had asked him what he thought he ought to do; that after some conversation, Charles had determined, and he agreed with him, that he ought to isolate himself entirely from the woman, and let another man take his place at her side; and this Charles had accordingly done, with a most praiseworthy spirit of selfsacrifice. Charles had indeed still further taken up his cross, as he had noticed with pleasure, by going to sleep with the smaller children, to take charge of them during the night. Taking all this in view, he thought Charles was in a fair way to become a better man, and had manifested a sincere desire to improve, and to rid himself of all selfish faults.[12]

Contraception

To control reproduction within the Oneida community, a system of male continence or coitus reservatus was enacted.[13] Noyes decided that sexual intercourse served two distinct purposes. The primary purpose was social satisfaction, "to allow the sexes to communicate and express affection for one another".[14] The second purpose was procreation. Of around two hundred adults using male continence as birth control, there were twelve unplanned births within Oneida between 1848 and 1868.[14] Young men were introduced to male continence by women who were post-menopause, and young women were introduced by experienced, older males.[15]:18

Noyes believed that ejaculation "drained men's vitality and led to disease"[16]:742 and pregnancy and childbirth "levied a heavy tax on the vitality of women".[16]:742 Noyes founded male continence to spare his wife, Harriet, from more difficult childbirths after five traumatizing births of which four led to the death of the child.[15]:17 They favored this method of male continence over other methods of birth control because they found it to be natural, healthy and favorable for the development of intimate relationships. If a male failed they faced public disapproval or private rejection.[16]:743

It is unclear whether the practice of male continence led to significant problems, although it is possible that masturbation and anti-social withdrawal from community were issues.[15]:19 It is believed that male continence did not lead to impotence in the community.[15]:18

Stirpiculture

Main article: Oneida stirpiculture

A program of eugenics, then known as stirpiculture,[17] was introduced in 1869.[18][19] It was a selective breeding program designed to create more perfect children.[20] Communitarians who wished to be parents would go before a committee to be matched based on their spiritual and moral qualities. 53 women and 38 men participated in this program, which necessitated the construction of a new wing of the Oneida Community Mansion House. The experiment yielded 58 children, nine of whom were fathered by Noyes.

Once children were weaned (usually at around the age of one) they were raised communally in the Children's Wing, or South Wing.[21] Their parents were allowed to visit, but if those in charge of the Children's Wing suspected a parent and child were bonding too closely, the community would enforce a period of separation.[22]

Role of women

Oneida embodied one of the most radical and institutional efforts to change women's role and improve female status in 19th-century America.[23] Women gained some freedoms in the commune that they could not get on the outside. Some of these privileges included not having to care for their own children as Oneida had a communal child care system, as well as freedom from unwanted pregnancies with Oneida's male continence practice. In addition, they were able to wear functional, Bloomer-style clothing and maintain short haircuts. Women were able to participate in practically all types of community work.[23] While domestic duties remained a primarily female responsibility, women were free to explore positions in business and sales, or as artisans or craftsmen, and many did so, particularly in the late 1860s and early 1870s.[4]:260 Last, women had an active role in shaping commune policy, participating in the daily religious and business meetings.[23]

The complex marriage and free love systems practiced at Oneida further acknowledged female status. Through the complex marriage arrangement, women and men had equal freedom in sexual expression and commitment.[23] Indeed, sexual practices at Oneida accepted female sexuality. A woman's right to satisfying sexual experiences was recognized, and women were encouraged to have orgasms.[4]:224, 232 However, a woman's right of refusing a sexual overture was limited depending on the status of the man who made the advance.[4]:241

Ellen Wayland-Smith, author of "The Status and Self-Perception of Women in the Oneida Community", said that men and women had roughly equal status in the community. She points out that while both sexes were ultimately subject to Noyes' vision and will, women did not suffer any undue oppression.[24]

Decline

The community lasted until John Humphrey Noyes attempted to pass leadership to his son, Theodore Noyes. This move was unsuccessful because Theodore was an agnostic and lacked his father's talent for leadership.[25] The move also divided the community, as Communitarian John Tower attempted to wrest control for himself.[3]

Within the commune, there was a debate about when children should be initiated into sex, and by whom. There was also much debate about its practices as a whole. The founding members were aging or deceased, and many of the younger communitarians desired to enter into exclusive, traditional marriages.[26]

The capstone to all these pressures was the campaign by Professor John Mears of Hamilton College against the community. He called for a protest meeting against the Oneida Community; it was attended by forty-seven clergymen.[27] John Humphrey Noyes was informed by trusted adviser Myron Kinsley that a warrant for his arrest on charges of statutory rape was imminent. Noyes fled the Oneida Community Mansion House and the country in the middle of a June night in 1879, never to return to the United States. Shortly afterward, he wrote to his followers from Niagara Falls, Ontario, recommending that the practice of complex marriage be abandoned.

Complex marriage was abandoned in 1879 following external pressures and the community soon broke apart, with some of the members reorganizing as a joint-stock company. Marital partners normalized their status with the partners with whom they were cohabiting at the time of the re-organization. Over 70 Community members entered into a traditional marriage in the following year.

During the early 20th century, the new company, Oneida Community Limited, narrowed their focus to silverware. The animal trap business was sold in 1912, the silk business in 1916, and the canning discontinued as unprofitable in 1915.

The joint-stock corporation still exists and is a major producer of cutlery under the brand name "Oneida Limited". In September 2004 Oneida Limited announced that it would cease all U.S. manufacturing operations in the beginning of 2005, ending a 124-year tradition. The company continues to design and market products that are manufactured overseas. The company has been selling off its manufacturing facilities. Most recently, the distribution center in Sherrill, New York was closed. Administrative offices remain in the Oneida area.

The last original member of the community, Ella Florence Underwood (1850–1950), died on June 25, 1950 in Kenwood, New York near Oneida, New York.[28][29]

Legacy

From a 1907 postcard

Many histories and first-person accounts of the Oneida Community have been published since the commune dissolved itself. Among those are: The Oneida Community: An Autobiography, 1851–1876 and The Oneida Community: The Breakup, 1876–1881, both by Constance Noyes Robertson; Desire and Duty at Oneida: Tirzah Miller's Intimate Memoir and Special Love/Special Sex: An Oneida Community Diary, both by Robert S. Fogarty; Without Sin by Spencer Klaw; Oneida, From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table by Ellen Wayland-Smith; and biographical/autobiographic accounts by once-members including Jessie Catherine Kinsley, Corinna Ackley Noyes, George Wallingford Noyes, and Pierrepont B. Noyes.

An account of the Oneida Community is found in Sarah Vowell's book Assassination Vacation. It discusses the community in general and the membership of Charles Guiteau, for more than five years, in the community (Guiteau later assassinated President James A. Garfield). The perfectionist community in David Flusfeder's novel Pagan House (2007) is directly inspired by the Oneida Community. Oneida Community is given tribute at Twin Oaks, a contemporary intentional community of 100 members in Virginia. All Twin Oaks' buildings are named after communities that are no longer actively functioning, and "Oneida" is the name of one of the residences.

The Oneida Community Mansion House was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1965, and the principal surviving material culture of the Oneida Community consists of those landmarked buildings, object collections, and landscape. The five buildings of the Mansion House, separately designed by Erastus Hamilton, Lewis W. Leeds, and Theodore Skinner, comprise 93,000-square-foot (8,600 m2) on a 33-acre site. This site has been continuously occupied since the community's establishment in 1848 and the existing Mansion House has been occupied since 1862. Today, the Oneida Community Mansion House is a non-profit educational organization chartered by the State of New York and welcomes visitors throughout the year with guided tours, programs, and exhibits. It preserves, collects and interprets the intangible and material culture of the Oneida Community and of related themes of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Mansion House also houses residential apartments, overnight guest rooms, and meeting space.

The Lancaster Glass Works opened in Erie County, New York, in 1849. During the next

32 years, a number of owners, mostly partnerships, operated the plant, making a large variety of

bottles and flasks – few of them with manufacturer’s marks. In 1881, a group of workers

purchased the factory, renaming it the Lancaster Cooperative Glass Works, a corporation. The

group reorganized in 1893 or 1894 and again in 1897, becoming a limited corporation or

partnership – although it reverted to corporate status in late 1898 or 1899. The plant may have

closed in 1903 or 1904, then reopened in 1907, but the business closed permanently ca. 1909.

Charles W. Reed and seven other glass blowers from Pittsburgh established the Lancaster

Glass Co. in Erie County, New York, in 1849, under the firm name of Reed, Allen, Cox & Co. –

and began making glass about the first of August at a single furnace and only five pots. The

company made flasks and many styles of bottles, including (but not limited to) beer, soda,

mineral water, ale, bitters – and even some pitchers and occasional other off-hand pieces (Bilotta

1970:5; McKearin & Wilson 1978:144).

Samuel S. Shinn acquired the interests of one or more of the owners, and Reed, Shinn &

Co. operated works from at least 1859, although the plant burned to the ground that year – to be

rebuilt almost immediately. In 1863, Dr. Frederick H. James purchased Shinn’s shares, and

Nathan B. Gatchell apparently bought the interest of one or more of the other owners.1

The firm

became James, Gatchell & Co. James and Gatchell purchased the remaining shares in mid-1864

and became a major producer of insulators – although none were marked with the glass factory

name. Tax records show James, Gatchell & Co. until March 1864, but the firm was James &

Gatchell by August. James acquired Gatchell’s interests in 1866 and operated the plant as the

James Glass Works until 1881 (McKearin & Wilson 1978:144; von Mechow 2017).

Toulouse (1971:433) correctly connected the Lancaster Reed with the Reed of the Clyde

Glass Co. ca. 100 miles to the east of Lancaster at Clyde. When Charles W. Reed left the

Lancaster Glass Works, he moved to Clyde in 1865 or 1866 to purchase Amon Wood’s share of

Southwick and Wood, becoming Orrin Southwick’s partner in Southwick & Reed. The firm

eventually became Ely, Reed & Co. in 1878, and Reed left in 1880 (see the section on the Clyde

Glass Works for more details). However, Toulouse was incorrect in assuming that this was the

same Reed family that started F.E. Reed & Co. at Rochester (although they may have been more

distant relatives). Charles Reed moved to Massillon, Ohio – not to Rochester – and opened Reed

& Co. there in 1881 (see the section on Reed & Co. for more on that firm).

(from PDF document, no copyright given, by Bill Lockhart, Beau Shriever, Bill Lindsey, Carol Serr, and Nate Briggs).

Nearby towns in Erie County :

Cities

Buffalo (county seat)

Lackawanna

Tonawanda

Towns

Alden

Amherst

Aurora

Boston

Brant

Cheektowaga

Clarence

Colden

Collins

Concord

Eden

Elma

Evans

Grand Island

Hamburg

Holland

Lancaster

Marilla

Newstead

North Collins

Orchard Park

Sardinia

Tonawanda

Wales

West Seneca

Villages

Akron

Alden

Angola

Blasdell

Depew

East Aurora

Farnham

Gowanda

Hamburg

Kenmore

Lancaster

North Collins

Orchard Park

Sloan

Springville

Williamsville

Census-designated places

Angola on the Lake

Billington Heights

Cheektowaga

Clarence

Clarence Center

Eden

Eggertsville

Elma Center

Grandyle Village

Harris Hill

Holland

Lake Erie Beach

North Boston

Tonawanda

Town Line

University at Buffalo

Wanakah

West Seneca

Hamlets

Akron Junction

Alden Center

Armor

Athol Springs

Bagdad

Bellevue

Big Tree

Blakeley

Blossom

Boston

Bowmansville

Brant

Brighton

Carnegie

Chaffee

Clarksburg

Cleveland Hill

Clifton Heights

Collins Center

Concord

Creekside

Crittenden

Dellwood

Derby

Doyle

Duells Corner

Dutchtown

East Amherst

East Concord

East Eden

East Elma

East Seneca

Ebenezer

Eden Valley

Ellicott

Elma

Evans Center

Ferry Village

Footes

Forks

Fowlerville

Gardenville

Getzville

Glenwood

Green Acres

Griffins Mills

Holland

Hunts Corners

Jerusalem Corners

Jewettville

Kenilworth

Lake View

Langford

Lawtons

Locksley Park

Looneyville

Loveland

Marilla

Marshfield

Millersport

Millgrove

Morton Corners

Mount Vernon

Murrays Corner

New Ebenezer

New Oregon

North Bailey

North Evans

Oakfield

Patchin

Peters Corners

Pine Hill

Pinehurst

Pontiac

Porterville

Protection

Sand Hill

Sandy Beach

Scranton

Sheenwater

Shirley

Snyder

South Cheektowaga

South Newstead

South Wales

Spring Brook

Swifts Mills

Taylor Hollow

Town Line Station

Swormville

Walden Cliffs

Wales Hollow

Water Valley

Webster Corners

Wende

West Alden

West Falls

Weyer

Williston

Windom

Wolcottsburg

Woodlawn

Woodside

Wyandale

Zoar

Indian reservations

Cattaraugus Reservation

Tonawanda Reservation

Towns in Oneida County :

Cities

Rome

Sherrill

Utica (county seat)

Towns

Annsville

Augusta

Ava

Boonville

Bridgewater

Camden

Deerfield

Florence

Floyd

Forestport

Kirkland

Lee

Marcy

Marshall

New Hartford

Paris

Remsen

Sangerfield

Steuben

Trenton

Vernon

Verona

Vienna

Western

Westmoreland

Whitestown

Villages

Barneveld

Boonville

Camden

Clayville

Clinton

Holland Patent

New Hartford

New York Mills

Oneida Castle

Oriskany

Oriskany Falls

Remsen

Sylvan Beach

Vernon

Waterville

Whitesboro

Yorkville

Census-designated places

Bridgewater

Chadwicks

Clark Mills

Durhamville

Prospect

Verona

Washington Mills

Westmoreland

Hamlets

Adrian

Cassville

Deansboro

Jewell

Lower South Bay

North Bay

Point Rock

Sauquoit

Taberg

Verona Mills

Westernville

Syracuse